No products in the cart.

Boats of Light Festival

Lai Heua Fai in Luang Prabang

Mara D’Andrea, TAEC Intern

When I first arrived in Luang Prabang, one of the most talked-about events was a festival that I was told not to miss for any reason. For weeks, I imagined what this celebration might be like. Finally I had the chance to both witness and participate in parts of the festival, experiencing the beautiful atmosphere of Boun Awk Phansa and Lai Heua Fai—also known as the “Boats of Light” Festival. For those curious about what to expect, here are some insights and reflections!

Boun Awk Phansa marks the end of “Buddhist Lent”. The exact date varies each year, as it follows the lunar calendar, but it typically lasts about three months, from the full moon in July to the full moon in October. During this time, people are encouraged to observe religious precepts more strictly. Monks and novices are not allowed to leave their temples after sunset, a rule originally established by Buddha himself to give the crops time to be restored after he and his followers had tirelessly walked on them.

Image #4: A fun mix of modernity and tradition at Wat Choum Khong Sourin Tharam

Though Lent emphasises meditation and prayer, in the weeks leading up to Boun Awk Phansa, monks and novices are still busy in their temples. They create beautiful and colourful paper lanterns that will adorn the temple grounds. Around town, more lanterns are crafted or purchased to decorate homes, shops, and restaurants during the celebration week. The streets are literally filled with lights.

On Boun Awk Phansa, early in the morning, people gather offerings typically of water, sticky rice, and Khao Tom (rice, coconut milk, and bananas wrapped and cooked in banana leaves) to take to the nearest temple for the tak bat ceremony. (Tak Bat is also referred to as “Sai Bat”, or in English as “almsgiving” – although it differs from almsgiving as we know it in other cultures and religions).

#1. Khao Tom ready to be cooked. #2. A variety of offers at Awk Phansa ceremony #3: Alms giving, Luang Prabang

After offering some of the food to Buddha, they sit together to pray under the guidance of monks, who eventually collect the food that has been prepared for them. This practice attracts larger crowds during special religious events like Awk Phansa, but a different version of it takes place regularly around Laos, each community has a different schedule, in Luang Prabang it occurs every morning around 6am on the main street. If you wish to participate, make sure you understand the meaning behind it and learn how to do so respectfully.

Being in Luang Prabang in the days leading up to Boun Awk Phansa is special in itself. The atmosphere is vibrant as the town is decorated. Walking through the centre during the day, you’ll hear the continuous chanting of ceremonies taking place at Phousi Mountain, the highest point in the town.

During this time, don’t miss the chance to visit the temples: monks light hundreds of lanterns, and you’ll be amazed by the variesty in their designs and displays. (Note: Remember that temples are still sacred spaces, so be respectful by dressing and behaving appropriately.)

Walking in between the lanterns you will see big snake-like figures made mostly of bamboo and paper. These are the Nagas, one of the key symbols of Boun Lai Heua Fai, also known as the Boats of Light Festival. The Nagas are serpent water divinities traditionally believed to inhabit rivers. They hold a significant place in Lao culture, embodying a blend of animist and Buddhist beliefs.

Like the Nagas, the festival carries a dual significance, celebrating both the end of Lent and the beginning of the dry season. To me, it seems these two aspects are symbolically united in Lai Heua Fai, connecting the temple and the river through the parade.

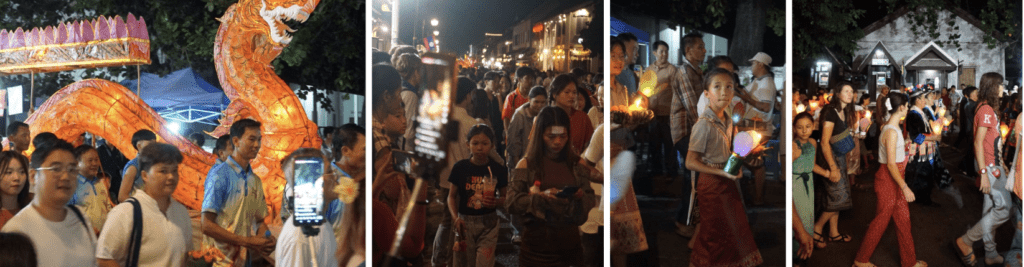

During Lai Heua Fai, various villages in the town carry the Nagas they have patiently crafted (often right at the temples) down the main street, showcasing them to the rest of the town and a jury that selects the most beautiful and resilient ones.

Watching the parade is an experience in itself. The spirituality of the festival blends with the high spirits of the people playing music, dancing, singing, and performing fire shows, all while carefully tending to the hundreds of lit candles inside the delicate paper Nagas.

Variety is central to the parade: not only do the Nagas come in different shapes and colours, but the people carrying them also represent a diverse range of ages, dress styles, and attitudes. Fancy-looking sinhs (Lao traditional skirts), high heels, colourful traditional hats, bare feet, and school uniforms all find their place in this vibrant event, contributing to the festival’s dynamic atmosphere.

The parade concludes near Wat Xiengthong, where the Naga Boats are lowered into the Mekong river, one by one. But the big boats are not alone as they float on the water; tiny decorated boats, called krathongs, are also released. Traditionally made from banana trunks, leaves, and flowers, these boats serve as personal vessels for the wishes of those who set them adrift. Krathongs can be crafted from scratch or purchased around town.

People light a candle on their krathong and let it drift away after sunset. The boat is meant to carry away negative energy and bad luck, while also serving as an offering to the Nagas in the river. This is often accompanied by a whispered wish and offerings such as money or rice, or something personal such as a piece of hair, or fingernail clipping. It symbolises a time to let go, release past hardships, and start anew with the moon, the light, and the flow of the river.

The view of the river at the end of the night is spectacular, with countless tiny luminous krathongs accompanying the beautiful Nagas, gently carried away by the current. Intimate and personal wishes blend with the results of community effort, reminding me of what makes this festival truly special. This mix of the sacred and the secular, the personal and the collective, locals and tourists, fire and water, it is truly an experience worth participating in!